We're always deliberate in creating direct and meaningful involvement in work, transferring ownership to others when appropriate. This is because we believe that enabling direct engagement, participation and co-design approaches can lead to better solutions and outcomes, with the benefits of opening up new thinking and ideas.

Here, we share our overall approach to co-design, what it is and isn’t, and why and when we use it. In future posts, we’ll talk about other ways we use participation in design and what that looks like in practice. A lot of the thinking and approaches outlined in this blog post were inspired by the work of KA McKercher.

What is co-design?

Co-design means bringing people who are affected by a problem together with frontline staff, experts, decision-makers and designers to create solutions.

It means designing things with — not for — the people who will be most impacted by change.

Two things are essential here:

- Bringing different perspectives together (other than our own) to explore ideas, and to make design decisions, including those who directly experience the problems we are trying to solve

- Using visual, creative and practical design methods to understand the human experience of problems and situations, and to make ideas and solutions real so we can learn through doing

Co-design brings different perspectives together to make design decisions

In most of our work, we might interview people with experience of a problem, or even involve them in a workshop to generate ideas and test solutions. This provides the evidence we as designers, consultants and clients use to make design decisions about things like:

- What issues are important and how they are described

- What problem we need to solve

- Which solutions are likely to be effective, benefitting people and society

Co-design is different because it means people that experience a problem also take part in these design decisions about what needs to change and how. They have ownership of the design process intended to solve the problem. This is an intentional shift to sharing power and building equity in the design process.

For example, if you want to use co-design to improve family hub services, you involve families in decisions about what isn’t working and how we overcome those problems.

This doesn’t happen on the side. For families to have influence, they need to be in the room, working directly with service and senior staff to make decisions about how to improve things. They need to change people’s minds and their understanding of an issue. This is where real transformation happens because it changes the relationships between staff in organisations and the people they serve.

Co-design must upskill people to take part

We can use co-design methods to cut through the talking that might happen in a typical meeting or workshop. But co-design also requires skilled facilitators and a focus on building the capabilities of the people we involve, so they feel confident to take part and challenge the things designers and decision-makers say. When we do this well, we create an environment where everyone has insight to bring and something to learn.

Why co-design is different from business as usual

Co-design is different from what we normally do in design because it brings people together to make decisions in a way that shifts the balance of power away from the highest paid people.

Usually, people who use services (citizens) and people who deliver them (frontline staff) become research or testing subjects. Their knowledge of the service or experience of a social problem is extracted to inform our decisions of how to design things differently, but they aren’t involved in actually making those decisions.

Co-design moves us beyond one-off workshops and user research. Significant effort is invested in bringing different people together and building relationships between them so they develop trust and empathy for one another. Over time, the people involved become more knowledgeable about the problem they’re trying to solve and the different points of view. This takes time.

Being clear about co-design versus participation

There are lots of situations where we see things unhelpfully, or incorrectly labelled as co-design. For example, co-design can be used to describe:

- Having separate workshops with different stakeholder groups

- Focus groups

- Consultation events to ask people’s opinions

- Workshops with senior staff

- Management meetings with resident representatives

While these are all examples of participation, they aren’t co-design when used as standalone activities because they don’t bring different groups of stakeholders together continually across the design process.

When we use co-design

We will always look to use co-design when there is a clear reason to involve people in a deeper way, we have adequate resources to deliver this approach well and our client partners are ready for this type of commitment and challenge to how they work.

Some essential questions to ask when trying to determine if co-design is the right approach for a project are:

- Are there people that care enough about this issue to want to be involved? — this often comes down to what is at stake and the answer is likely no if you’re dealing with the design of a more transactional service

- Is it appropriate in this context? — for example, if you’re redesigning support services it might not be appropriate to involve people in design while they’re going through something difficult or traumatic

- Is it worth people’s time and what can we give them in return? — if you’re not providing accessible, worthwhile opportunities to citizens and rewarding their contribution in some way, you’re not creating the level playing field you need to co-design

- How will organisations taking part change as a result of this work? — you must be clear about the decisions that co-designers will get to influence and how to ensure that genuine change is possible

Exploring co-design further

It’s important to remember that fully committing to co-design is an involved process. It takes significant time and resource, skilled facilitation and careful planning to make sure that people who experience a problem influence decisions and benefit from being involved.

With sensitive topics like poverty, race or mental health, there is also a lot at stake and we risk doing more harm than good where there isn’t really scope for people to influence decisions or the resources to involve people well.

If you’re interested in reading more about real examples of co-design in practice, you can read about our recent work with YoungMinds improving access to mental health support for young Black people.

We are grateful to be doing more of this work with our clients and partners, and look forward to sharing more examples of how we’re applying co-design in practice.

If you’re interested in exploring this type of work with TPXimpact, contact ben.holliday@tpximpact.com

Our recent design blog posts

Transformation is for everyone. We love sharing our thoughts, approaches, learning and research all gained from the work we do.

-

Naming services in complex situations

Read blog post -

Using inclusive research approaches with Blood Cancer UK

Read blog post -

Designing for users who don’t exist (yet)

Read blog post -

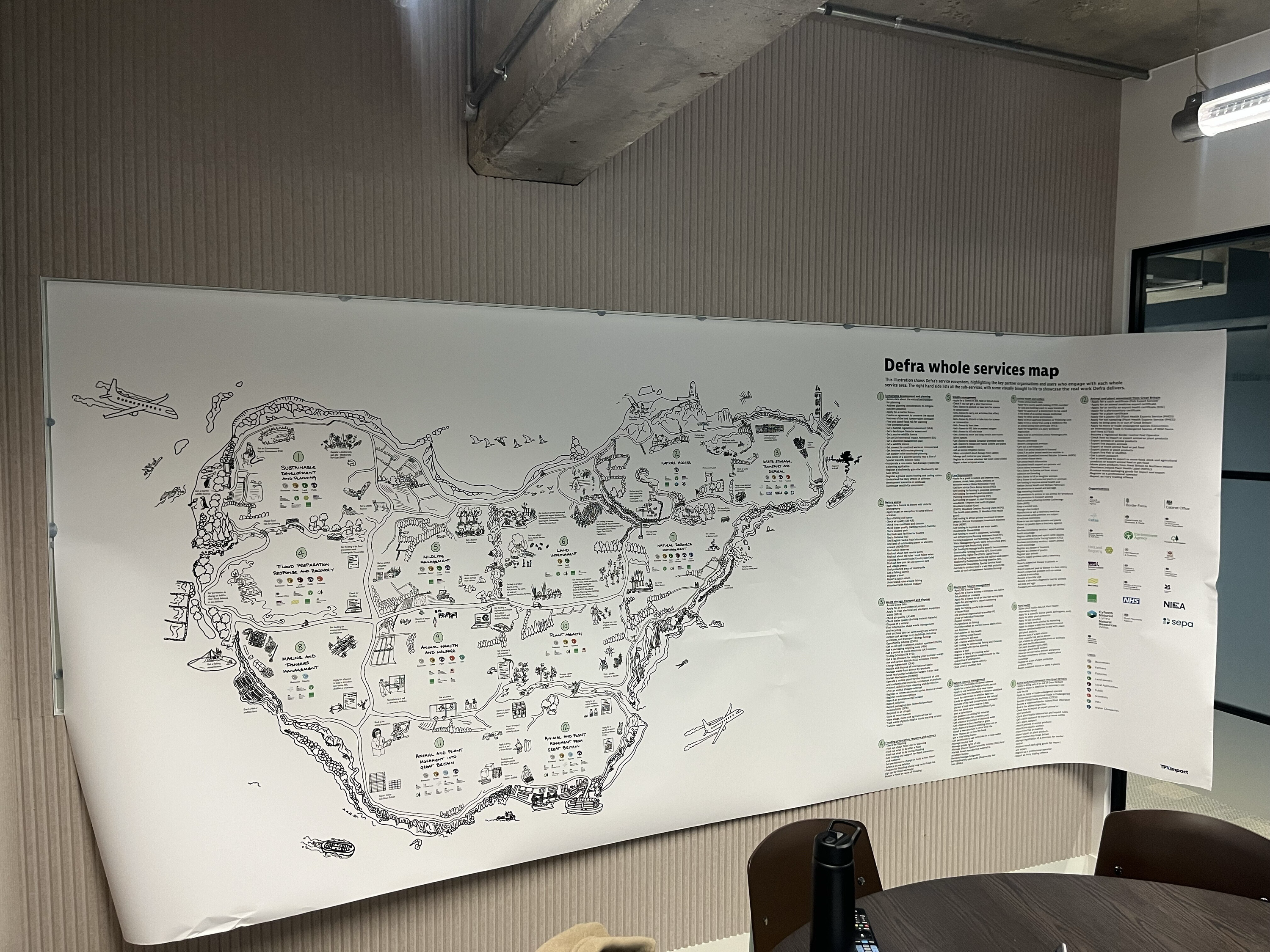

Beyond a blueprint: Visualising whole service areas

Read blog post